Triumph of Thanatos

These life-sized embroidered tapestries create an intriguing blend of delicate stitching and death. Here, the gods and godlike creatures are portrayed as death itself, serving as a symbol for the absence of an afterlife, denying the concept of immortality. This representation underscores the idea that even the most powerful beings are subject to the inevitability of death, and that all things must eventually come to an end.

Vesna

In early Slavic mythology, Vesna was a goddess who represented youth and the arrival of spring. She was especially revered in places like Croatia, Serbia, North Macedonia, and Slovenia, where she and her male counterpart, Vesnik, played a central role in springtime rituals in rural communities.

Here, Vesna is reimagined as the embodiment of death, her skeletal form blooming with delicate wildflowers. This piece brings to life a piece of forgotten Slavic history—the goddess herself. The halo around her symbolizes the myths that have come to replace her over time, while the goat head ties the image back to ancient Roman influences and the nature deities that once flourished in this region.

Ammit: The Devourer of Souls

In ancient Egyptian mythology, Ammit was the fearsome hybrid creature who awaited the souls of the dead at the threshold of eternity. Her form—a terrifying fusion of lion, hippopotamus, and crocodile, the three most dangerous beasts known to the Nile—reflected her singular purpose: to consume the unworthy.

At the heart of the afterlife was the Weighing of the Heart, a ritual presided over by Anubis and judged by the goddess Ma’at. The heart of the deceased was balanced against Ma’at’s feather—a symbol of truth, harmony, and cosmic order. Only if the heart was lighter or equal in weight could the soul pass on to Aaru, the Field of Reeds. But if the heart was burdened by lies and wrongdoing, Ammit would feast upon it, condemning the soul to a second, permanent death.

This textile piece reimagines Ammit not just as a beast of punishment, but as a gatekeeper of balance—fierce, unrelenting, and essential. Her powerful form is rendered through embroidery and appliqué, layered over a background made using the couching technique to form a pattern that recurs throughout my work—a quiet, almost subconscious signature. Patchwork elements reflect the fragmented, trial-based journey of the soul, while her hind legs—crocheted and dyed with black tea—introduce a raw, organic texture, evoking both decay and transformation.

Behind Ammit looms a red Aton—a glowing disc that can be seen either as a divine halo or a more unsettling image: Ammit reaching to devour the sun itself. It’s an open question. Does she hunger for the divine, or is she simply becoming it? Ammit may be a monster, but she is also justice. She does not hunt; she waits. And when she devours, it is not out of cruelty, but to uphold the sacred balance of the universe.

Daphne

The myth of Apollo and Daphne is a story full of passion, conflict, and transformation. It all begins with a rivalry between Apollo, the sun god, and Eros, the god of love. Eros shoots two arrows—one to spark love, the other to extinguish it. Apollo is struck by the arrow that ignites passion, while Daphne is hit by the one that suppresses it.

Daphne, the daughter of the river god Peneus, is devoted to the wildness of the forest and the ways of Artemis. She desires to remain untouched by love, even though her beauty draws suitors. No matter how much she wishes to stay free, she can’t escape their pursuit.

When Apollo falls under the spell of Eros’s arrow, he becomes infatuated with Daphne. He chases after her, despite her rejection, but no matter how fast he runs, she evades him. She begs her father for help, and in a desperate act to escape, she begins to transform. Her body turns to bark, her arms become branches, and her legs sink into the earth, becoming roots.

Even in her new form, Apollo's obsession doesn’t fade. Though she has rejected him, he vows to honor her forever. He uses her evergreen leaves and wood for his crown, bow, and lyre.

What began as a large hand-embroidered textile has since undergone its own metamorphosis, becoming part of a quilt through cutting, layering, and stitching. The embroidery is not replaced but recontextualized, its story continuing through a new form. You can view this latest textile art piece and its evolution into a quilt here

Anubis

Anubis, the ancient Egyptian god of funerary practices and protector of the dead, is often depicted as a jackal or as a man with the head of a jackal.

In the Early Dynastic period and Old Kingdom, Anubis held a leading role as the ruler of the dead, but over time, his prominence was overtaken by Osiris. Anubis was believed to have invented the art of embalming, which he first used on the body of Osiris.

To the ancient Egyptians, the decay of the body meant the soul’s disappearance—being forgotten was their greatest fear. To protect against this, they turned to Anubis, praying for the preservation of their physical form after death. Despite his association with embalming, this god is depicted here as a skeletal figure, alluding to the fact that he himself is not immune to the eventual clutch of death.

The inclusion of the ankh in Anubis’s hand creates a powerful contrast: it represents life, while his skeletal form points to the inevitable decay of the body.

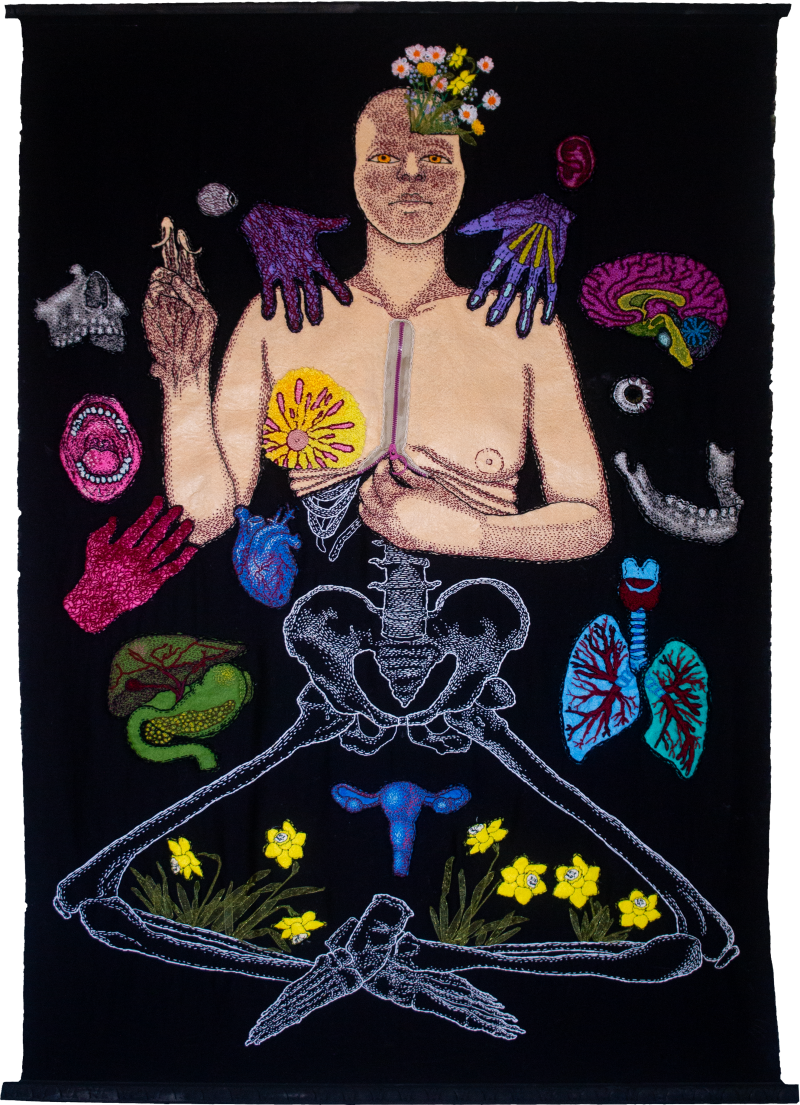

Cadavre Exquis

This fabric collage is a deeply personal self-portrait that captures the fragility and impermanence of the physical self. The rich textures and vibrant colors pull you in, creating a mesmerizing and almost hypnotic effect.

The artwork challenges viewers by incorporating dissected anatomical elements, aiming to evoke a sense of discomfort. It’s a reminder that art is meant to push boundaries, stir emotions, and spark reflection on who we are and how we see the world.

The title "Cadavre Exquis" (or "Exquisite Corpse") dates back over 100 years to the surrealists, who coined the term for a creative game similar to "consequences." Participants would take turns drawing or writing on a sheet of paper, folding it to hide parts of the work and passing it on for others to contribute. This evolved into "Picture Consequences," where the drawing of a figure was completed in stages, with each part hidden from the next participant.

In a similar spirit, this piece was crafted in separate stages, with each element designed and embroidered individually before being assembled into its final form. The result is a surreal and metaphysical piece that feels both fragmented and whole at the same time.